As Franz and I speak over Zoom, I can’t help but think about how much I’d enjoy drinking a beer with him in the sweltering heat of Santo Domingo while having this conversation. Franz speaks of the duality of being from the Dominican Republic, the foreign eye and the perception which is often attributed to the Caribbean, and I can’t help but feel part of it. Leaving the island has changed my perception of it, cementing the fact that this idea of a tropical paradise that I know is not real. The grass is always greener, is it not? As Franz talks to me about the contrast of the perceived Caribbean and the everyday reality of it, I’m starkly aware of what he means. All of a sudden, his work clicks.

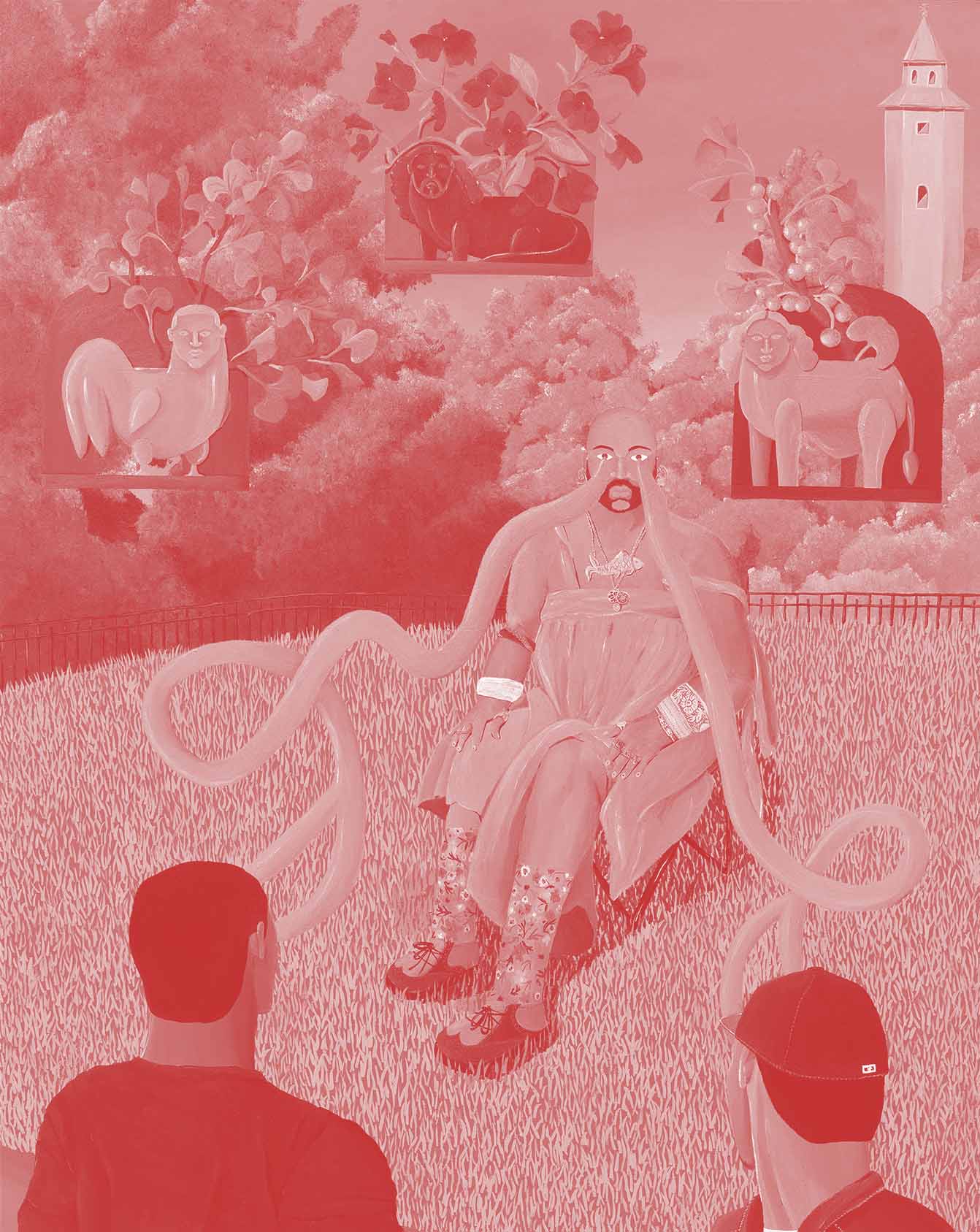

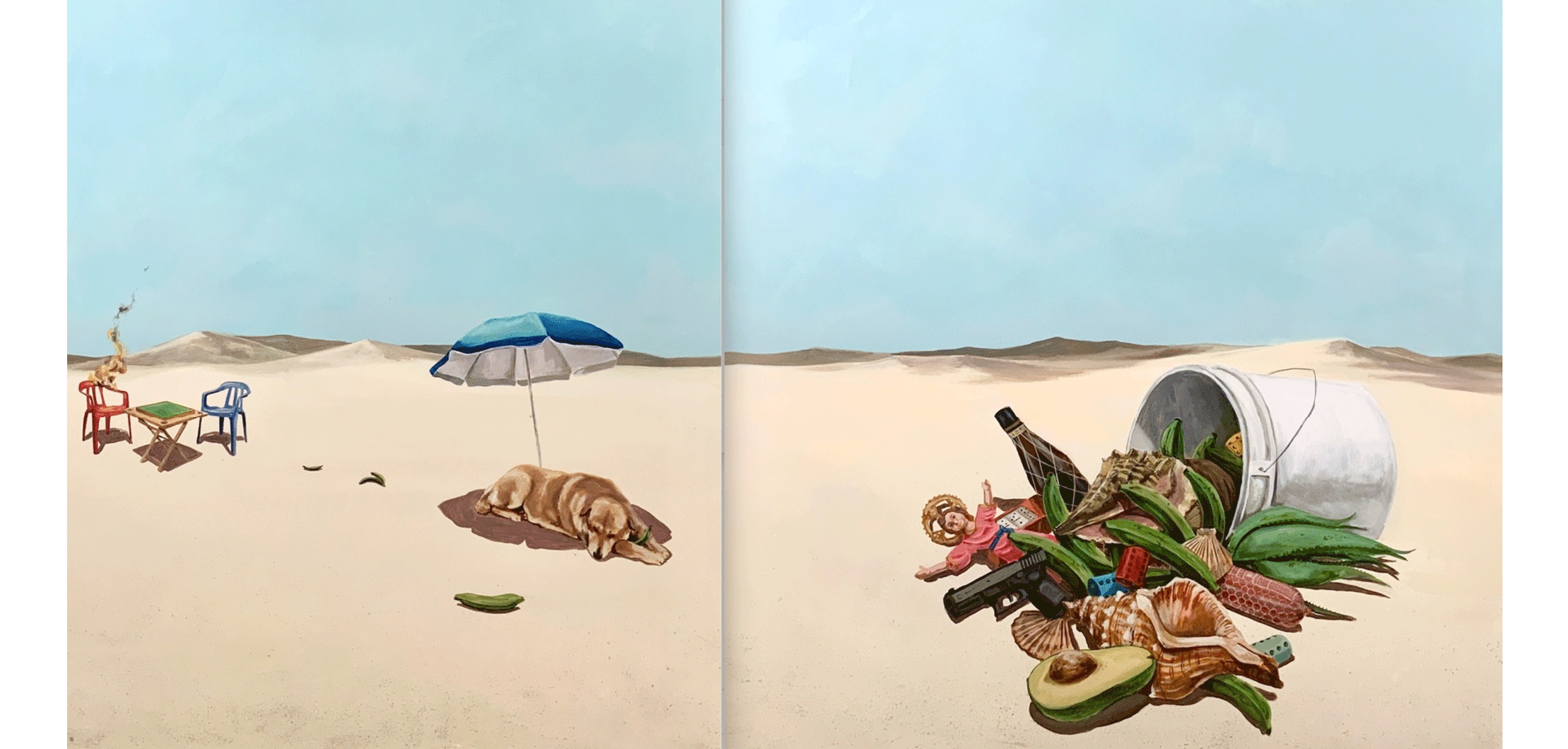

Franz Caba is a painter from the Dominican Republic. His work has deep roots in Dominican pop-culture, often featuring iconic imagery such as the plastic colmado chairs, the viralatas (or stray dogs) and the impossibly cramped buses that brave their way through the streets of Santo Domingo. Drawing influence from Japanese animated media, Franz’s work attempts to capture a still image that fits into a bigger story, something that becomes clear as soon as you see the movement in his work. Each scene presents the audience with a story, using subjects, landscapes and action to evoke a narrative structure in the still images.

As a Dominican who has become part of the diaspora, Franz’s work possesses something special to me. It takes those minute details of everyday Dominican life, and throws them in my face, reminding me that the tropical utopia I often tend to fawn over is more of an illusion than anything else. The plastic chairs remind me of the warm, yet chaotic atmosphere of a colmado. The viralatas remind me of the barking and the occasional friendly encounter. The buses remind me of the Santo Domingo traffic, the endless bottlenecks and the blaring horns under the scorching Caribbean sun. Franz takes these key elements of the minutiae of the Dominican mundanity and mashes them together with the fantastic portrayals that make his work so unique. We see those same plastic chairs gracefully rearing. We see the colmado bikes engaged in fierce battle. We see the coquero truck bracing the rough ocean waves, or a banca in an island in the middle of nowhere. This is, to me, Franz’s work. An amalgamation of contrasts.

In my conversation with Franz, I had the chance to probe the mind of one of the kindest, smartest, most interesting artists I’ve had the pleasure to meet. Not only is his work beautiful and ingenious, but the mind behind it is one capable of interpreting, and more importantly, reinterpreting reality in a way that truly encapsulates what it is to be “the other” when the other comes from home, and what it is to miss the thing you always dreamed of getting away from.

How did your journey with painting start? Was it something that always interested you, or did your interest develop through other means?

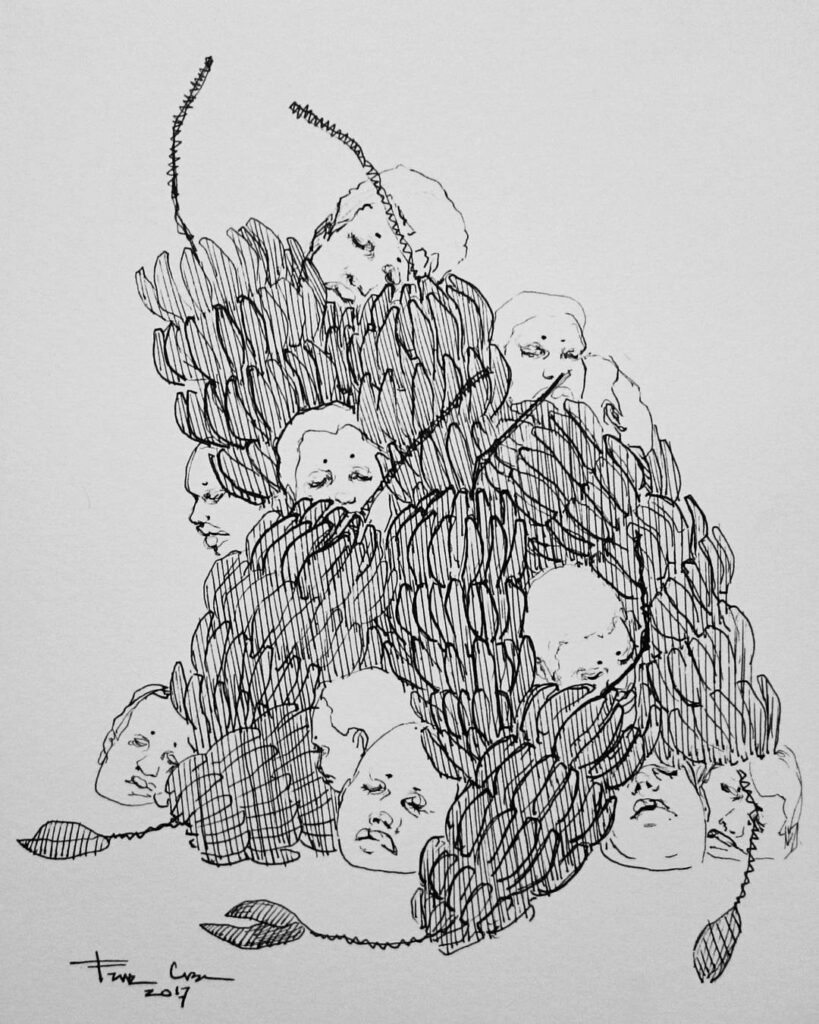

In all honesty, painting wasn’t a medium that particularly caught my attention. I first got interested in drawing, as I thought it was the most organic way to approach the production of images. My interest stems from two things: boredom and foolishness.

After spending most of my life drawing, I somehow wanted to try other methods of work, and painting attracted me because of its technical complexity. It felt like a good way to reset my creative process, and it led me to understand that painting was the most favorable medium for my current body of work.

When we first spoke, you mentioned the idea of an “imaginary Caribbean” that permeates your work. Can you elaborate more on this “imaginary Caribbean” and its contrast to what Caribbean/Dominican culture is for you?

I think that the Caribbean and the condition of being a Caribbean person lives in duality. Through time and the process of colonization, exploitation and commercialization of this territory, some fictions have come to birth through the foreign eye in order to satisfy the ideas and the wish of an earthly paradise that is accessible. These fantasies are a stark contrast from the ways of life and the realities that surface in the palpable Caribbean, and they transform the way we are perceived and the way we relate to our space.

When I went to Aruba in 2018 to participate in Caribbean Linked’s artist residency program, I went in with the preconceived idea that I was going to find a travel-postcard paradise. The everyday reality of the Aruban territory and its people differs greatly from the image I had in my head. This made me question the Caribbean I came from, and the reason for my expectations.

When we first spoke of your main artistic influences, you mentioned that a big part of it was Japanese art such as anime and manga. Can you elaborate on how these genres affected your style and work?

Lacking an academic artistic education, most of my source matter comes from Japanese animated media. I’ve always admired the way manga and anime artists use their visual

resources to narrate. This has always informed the way in which I approach image production. I like to think that the way in which I produce my work is via manga vignettes or frames of animation, where the frozen image I’m trying to portray belongs to a greater sequential narrative that has the capacity to introduce observers into the narrative arc. Through these mediums I discovered the potential of fantasy and Ero guro to approach about the earthly.

In your latest collection “Estoy aquí pero no soy yo”, many of the paintings use traditional imagery from Dominican popular culture, such as plastic chairs, stray dogs, buses, colmados and bancas. Is there any specific idea you were trying to communicate with the use of this imagery?

Unlike my past series’, where the main subject of the work was always the human corporeal figure, in Estoy Aquí Pero No Soy Yo, I discard corporeality, understanding that objects, animals, and landscapes have the ability to speak about our identities and realities while also referencing the bodies that relate to them. With this series of works I try to explore issues of belonging, otherness, the space and the identities of the Caribbean that have been constructed and imagined since the fantasies of colonization and tourist exploitation.

Usually, through the representation of landscape, I try to reflect about the fictions that create part of the context that I belong to and inhabit, one in which I often cannot see myself. I treat these landscapes as theater stages; I’m not interested in them looking particularly organic. I build them from Google searches, images from newspapers, Tinder profiles and personal files, to which I then add the elements of animals, objects and buildings to mix my personal anecdotes with observations and collective cultural and sociopolitical questions.

Not long ago you joined Lucy García’s (Dominican Gallerist) roster of artists. Have you noticed a significant impact in your career stemming from this?

I think the biggest impact of joining Lucy García has been the introduction and consolidation of my art to the collector’s atmosphere that, in one way or another, would’ve been hard to access. Also, the curatorial aspect of Lucy’s gallery, with her amazing curator Orlando Isaac, with whom I’m constantly working with when it comes to curating my work and getting feedback.

Being a Dominican artist living in the DR is very different from being a Dominican artist living abroad. Have you noticed any challenges that the Dominican artist living in the DR tends to struggle with?

Both Dominican artists and their work are faced with a system that completely ignores the craft. The lack of state or private incentives that go beyond biennale events, plagued by very timid and “safe” collecting, and the lack of experimental exhibition spaces make the development and consolidation of art as a career very difficult for artists.

When we first spoke, we talked about Dominican artists abroad and their support for art based in the country. In your opinion, do you believe that local Dominican art and Dominican art from abroad form part of the same community or movement, or are the two separate from one another? Why or why not?

I think every group responds to their own context. Keeping in mind that many of the Dominican artists that belong to the diaspora share their conceptual interests and practices with local artists, and that there is a certain professional and personal kinship between them, the marked differences in resources and opportunities seem to be strong enough to separate what can be done here and what can be done “there.”

One of the biggest struggles that Caribbean/Latinx artists go through is that of separating themselves and their work from the stereotypical connotations of their culture. What is your opinion on Latinx artists’ work being valued exclusively for their perceived representation of Latinx culture?

I think there is a serious issue of Latin-Americans being pigeonholed and validated only inside certain visual discourses and contexts. At one point, I had the opportunity to participate in an exhibition with my previous body of work, and one of the things that shocked me the most was hearing that “it didn’t look Caribbean”. Those words led me to question the imaginary tropics through its own representation. I think that a great part of this problem comes from the exotification and exploitation of our cultures, contexts and the people that habit them.

If you had to choose one artist, from any medium, that you think everyone should know, who would that be and why?

Lately I’ve been studying Cuban artist Belkis Ayón’s work. I think the narrative richness and the visual aspects of her work have the ability to transcend barriers. I’m in love with all her work.

Edited by Andrea Bautil