Tu formación académica es extensa y diversa, abarcando desde la Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo hasta la Universidad de Harvard. ¿Cómo han influido tus variadas experiencias educativas, en tu enfoque curatorial y en tu carrera en general?

Ha influido en todo, tanto mis estudios de publicidad, diseño, cine y más recientemente mis estudios en investigación sobre “Afrodescendecia y derechos humanos”, me ha permitido ver la curaduría de una manera más amplia, mucho más humana, como un todo, donde cada elemento no puede estar separado de otro, desde la investigación propia que se da al momento de embarcarme en un proyecto en donde visualizo todo para que funcione ya sea en un espacio museal o intersticial. La curaduría, es una profesión que depende mucho de todo lo que puedas sumar, y tener estos conocimientos me permiten de que cualquier mínimo detalle desde la ficha narrativa, las visuales, el color, lo espacial puedan convivir de una manera cohesionada y única, para que cada proyecto expositivo tenga su propia identidad.

¿Cómo empezó tu trayectoria con la curaduría? ¿Cuál fue tu primera oportunidad que empezó a definir tu carrera?

Yo empecé a curar sin darme cuenta que estaba curando, porque no estaba familiarizado con esto, a través de los libros de arte que diseñaba comencé a conocer a cada artista y su mundo, cada gestor cultural, cada institución, y siempre pedían mi opinión de cómo hacer las cosas para que funcionen dentro de un espacio, o como yo veía tal proyecto, y de alguna manera yo decía como yo lo veía y les decía porque, y cuando iba a los opening, para sorpresa mía encontraba las obras que habíamos conversado en el lugar indicado, hasta las paredes incluso con el color que les había sugerido.

Pienso que fue una expo que se titulé “Weather, Lines, Video and Tape” en la Galería de Lucy García, ella me pidió que hiciera una colectiva y que la asumiera con total libertad, en esta expo plantee desde el naming, hasta los artistas que debían participar, incluso algunos que no pertenecían a la galería pero eran necesarios para muestra, fue una exposición maravillosa, increíble y con una buena vibra de todos, todas y todes, como pocas veces he experimentado.

La retrospectiva de Iván Tovar, fue la primera exhibición así en República Dominicana, correcto? Háblanos sobre el proceso de llevar a cabo una exposición tan impactante.

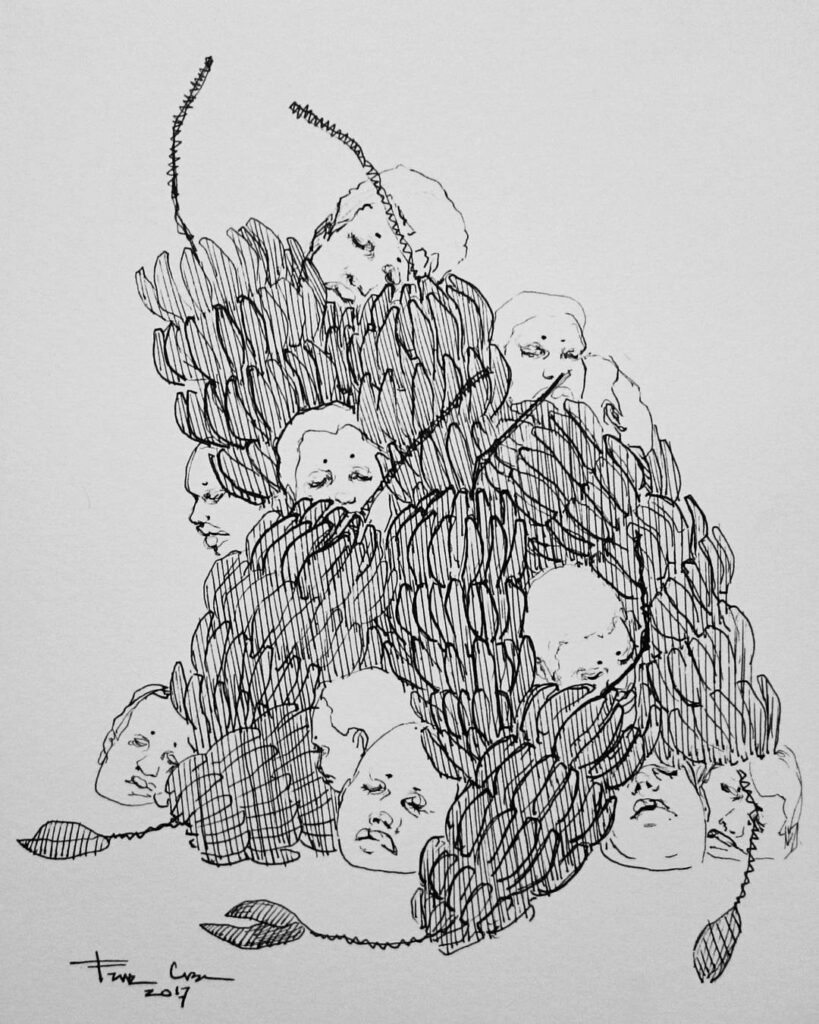

Wow, esa expo me ha marcado y pienso que me marcara toda la vida, el día que me llamarón para formar parte del equipo acababa de venir del cementerio de despedirme de mi mentor y amigo Jorge Pineda, el cual para mí era mi mayor consejero, el amigo con el que hablaba todo el día, en fin… fue muy raro todo. Ya había hecho una pequeña exposición de Iván Tovar en el 2019 en la Galeria de Lucy García, creo que fue su última muestra estando vivo. Recuerdo que fue un sábado que recibí la llamada de María Castillo viuda de Iván Tovar, me agarro por sorpresa y me hizo la pregunta que si me interesaba participar en esta gran exposición, sin pensarlo le dije que sí, yo quería escapar de mi dolor por la muerte de mi amigo. Ella me dijo que necesitaba consultarlo con el gestor no me dijo su nombre (Don Héctor José Rizek), antes de darme el sí, me dijo que él estaba de viaje que me avisaría los próximos días, media hora después sonó mi teléfono y me dijo bienvenido al barco y al otro día domingo en la mañana estaba en la casa de María, ella me mostro la parte más íntima de Tovar, desde sus bocetos, recortes de prensa, sus escritos a puño y letra, su ropa, sus recuerdos íntimos, y saliendo de casa de ella me fui al MAM, y lo visualice todo en esa hora que recorrí el museo, imaginé cada espacio y como quería narrarlo visualmente, recuerdo que pensé en un concepto mientras hacia el recorrido, “La curva, el color, la palabra y el asombro” y así lo mantuve, teníamos el tiempo en contra y una fecha ya anunciada, por los próximo 57 días no supe de mí, tenía que hacer el trabajo de investigación como si de años se tratara, yo me interne en la casa María, me fui a los depósitos de don Héctor José Rizek, fui al antiguo apartamento de Tovar y ella, allí vi su ropa, su silla de bambú, sus carboncillos, establecí contacto con personas que tenían otras obras que no estaban en el inventario y se agregaron, las obras fueron validadas por la restauradora, me dieron libertad para formar mi propio equipo, recibí el apoyo de todos, cuando inauguramos me sentí muy orgulloso de la gran exposición que habíamos logrado.

La curaduría editorial es una gran parte de ti. De dónde surge esta pasión?

Recuerdo una charla de Henry Wolf en el Dominico Americano, cuando yo entraba a la escuela de diseño de Altos de Chavón esta conferencia cambió mi manera de ver el mundo editorial y darme cuenta que había un mundo inmenso a través de los libros y como yo podía jugar con ellos. Los libros son para mí como un espacio expositivo fuera de los tradicionales (Museos, Galerías de Arte, Centro Culturales) por que las exposiciones pasan más el libro queda como un documento perenne y no efímero.

Cada libro que hago es una nueva oportunidad para yo poder crear y manifestar a través de sus páginas una secuencia narrativa de lo que sería otro modo de ver, mirar y observar.

¿Cómo equilibras los proyectos curatoriales con los editoriales, y qué desafíos y recompensas únicas encuentras al curar libros en comparación con exposiciones?

Dicho de una manera simple, me encanta la idea de que el público pueda entrar en el espacio expositivo físico y sentir la magia del artista y como el arte puede ser un eje transformador, cambiar tu percepción y el significado de la realidad. Esa manera de ver al espectador recorrer un espacio son momentos indescriptibles para un curador, es una gran responsabilidad poner en valor y respeto la obra de un artista y magnificarlo en su justa dimensión a través de una selección de piezas que puedan dialogar en la sala, que vienen precedidas de un arduo trabajo de meses con el artista o la institución.

Con el libro… lo llevo en mi ADN, es una extensión de mí, de lo que por tanto años hice y sigo haciendo, pero ahora soy mucho más consciente al verlo no solo como un documento que revive los sentidos desde la impresión, la memoria ocular, lo táctil, convirtiéndolo en algo objetual, una obra de arte también.

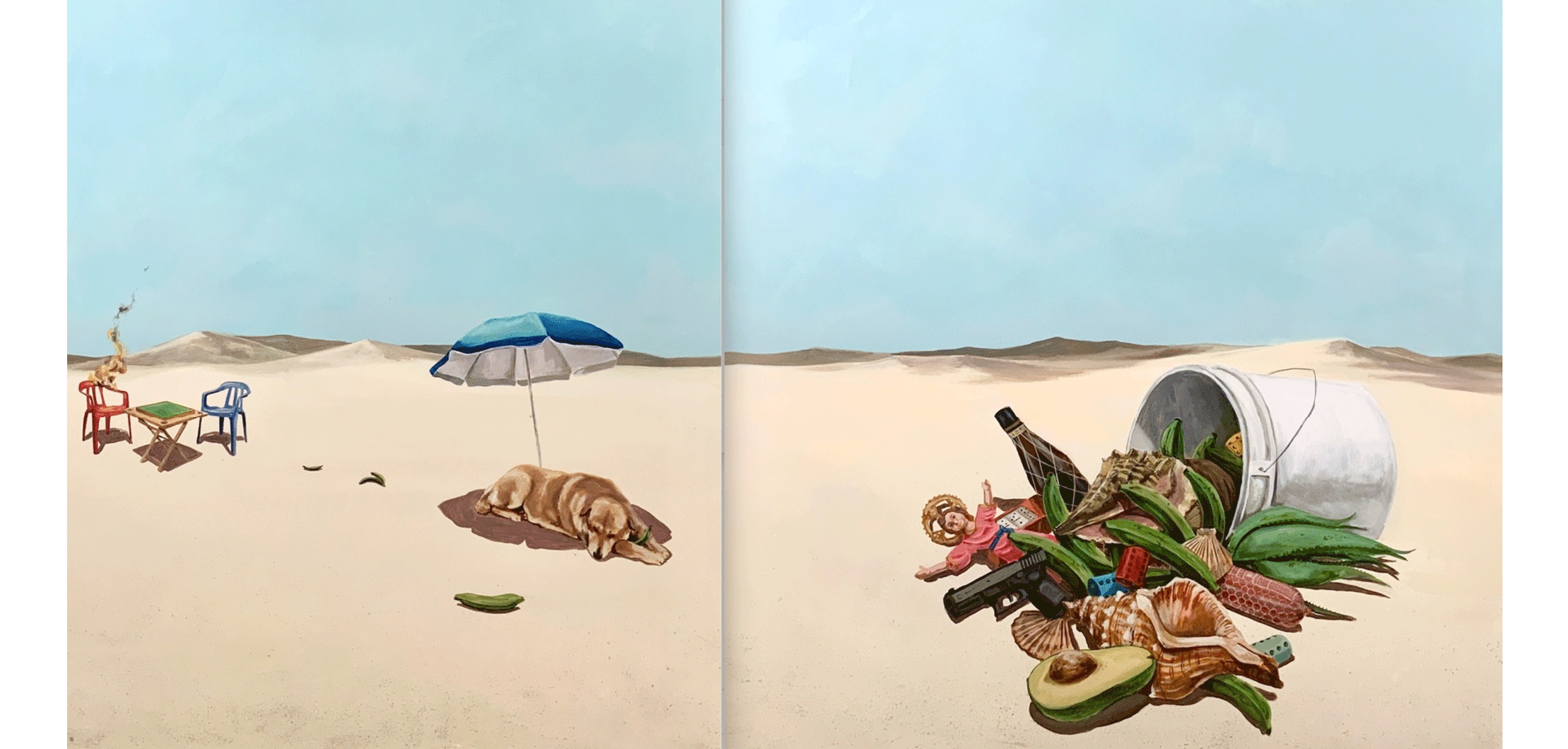

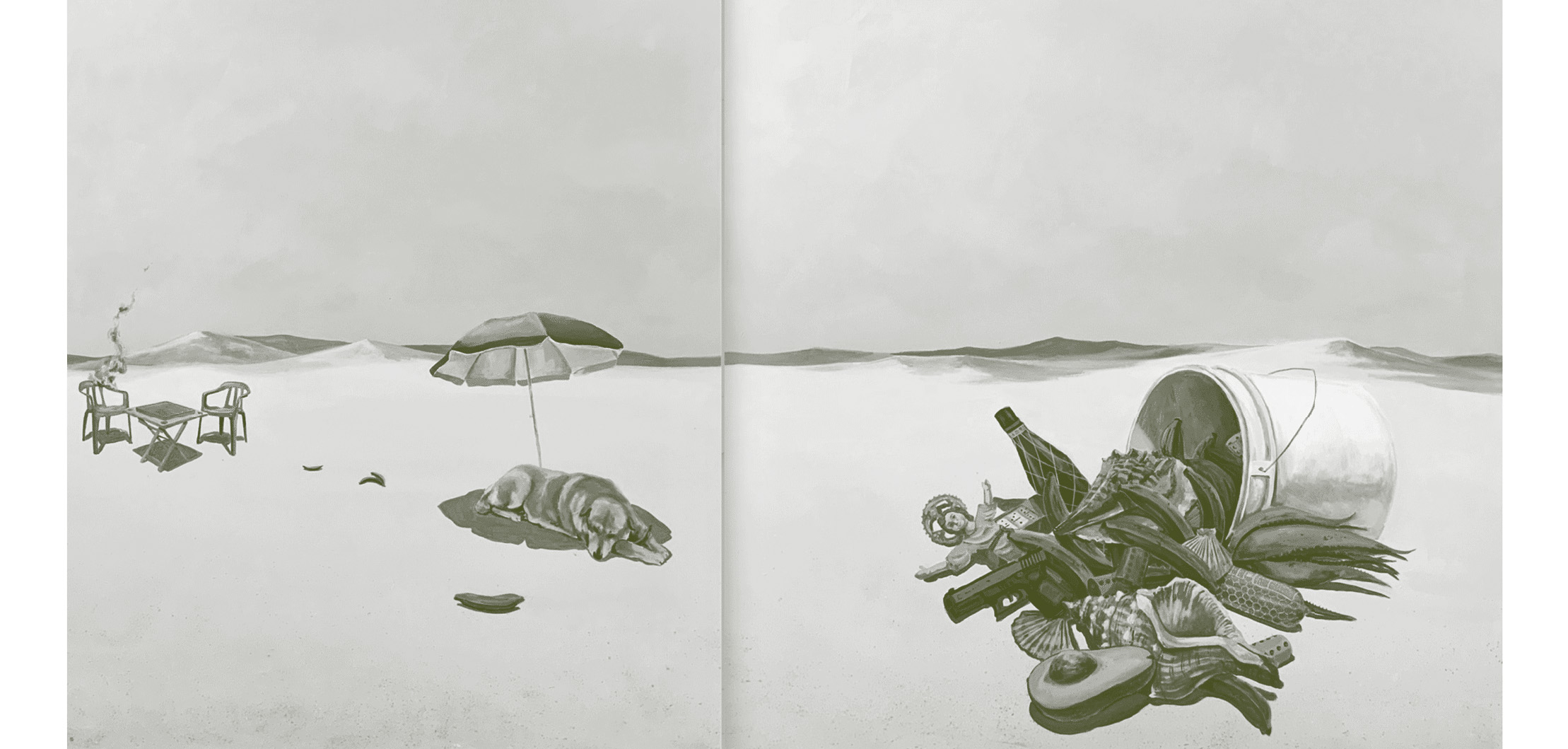

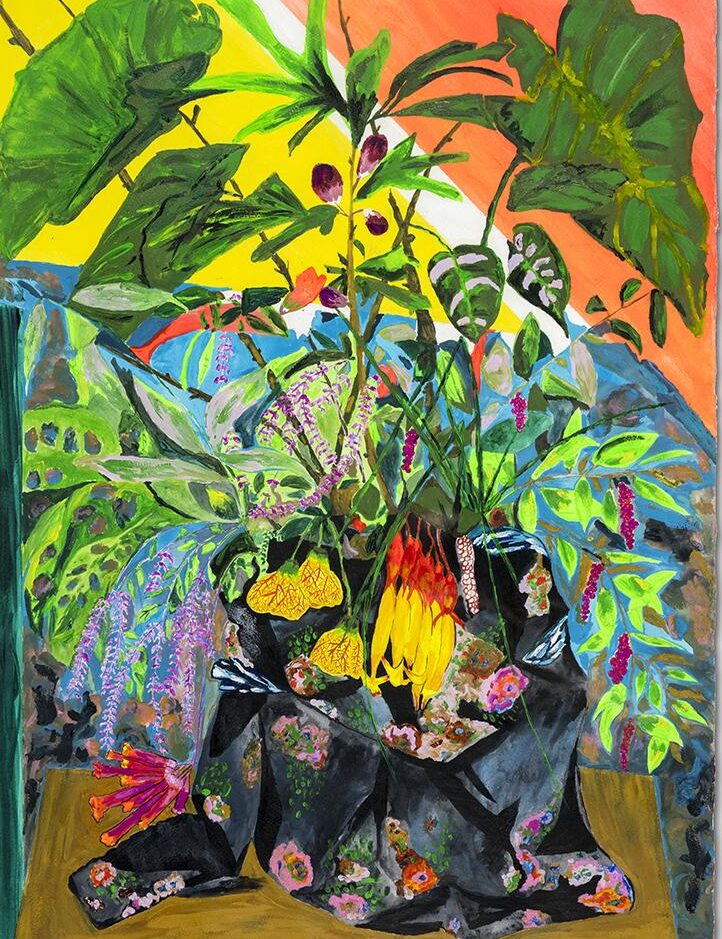

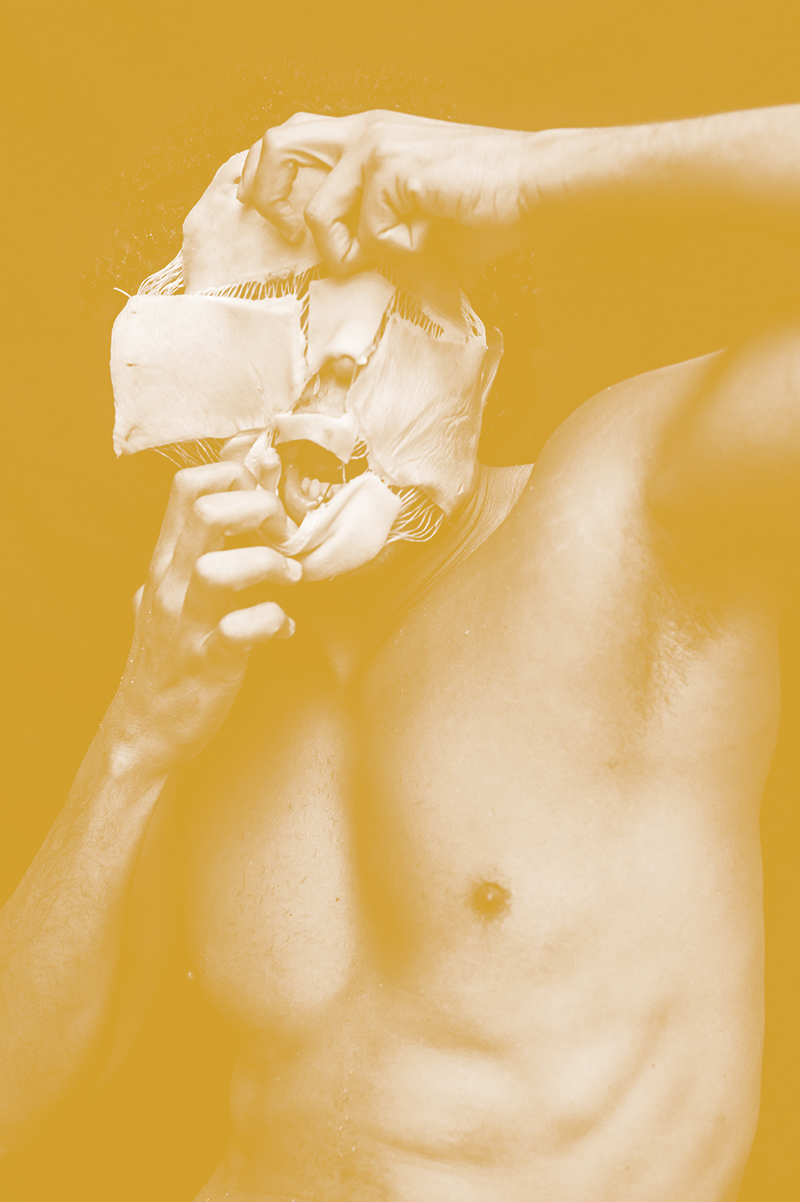

Has trabajado numerosas exposiciones, incluyendo recientemente “Amor, Amor: Pulsaciones de la Tierra, la casa y la piel” y “Niebla Rosa, Nave Azul” en 2024. ¿Podrías hablar sobre los temas y las visiones artísticas detrás de estas exposiciones recientes? ¿Cómo abordas el proceso de curar una exposición desde la concepción hasta la realización?

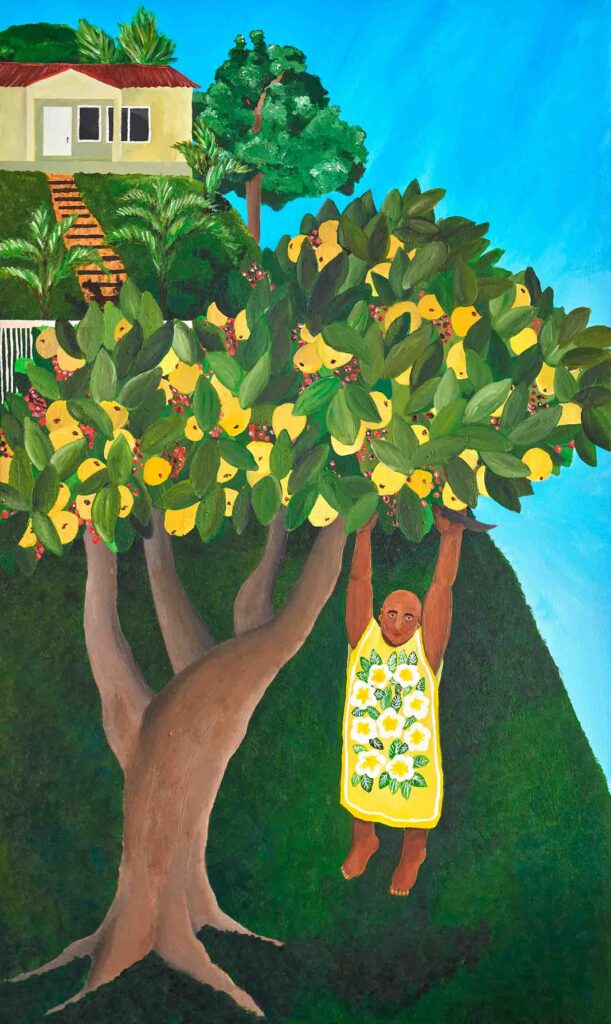

Estas dos exposiciones de dos magnificas mujeres artistas, sensibles, pero bien estructuradas a la hora de saber lo que quieren, para mí una cualidad única en la mujer, tanto Raquel Paiewonsky y Melissa Mejía, son dos artistas muy diferentes en cuanto su planteamiento estético, conceptos, feministas en sus propias cosmovisiones, diferentes en muchos aspectos pero de una integridad y compromiso indiscutible y para suerte coincidieron en una misma fecha, con cada una llevaba alrededor de un año de acompañamiento.

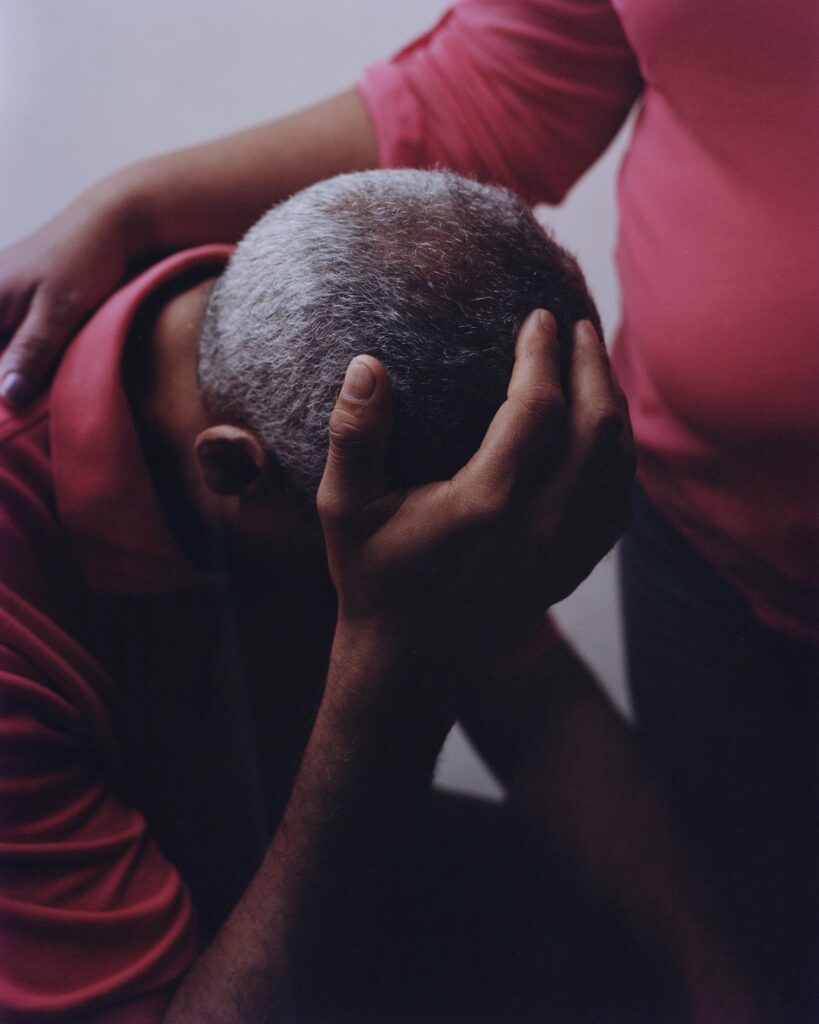

Con Raquel me embarque más en el diseño expositivo, en el venue, la identidad, el recorrido, el color, el espacio, en las cartelas como quería que se vieran y se leyeran las fichas narrativas, así como en la inclusión de algunas obras que para mí eran necesarias para contar esta expo que manejamos desde cuatro ámbitos: el amor, la tierra, la casa y la piel.

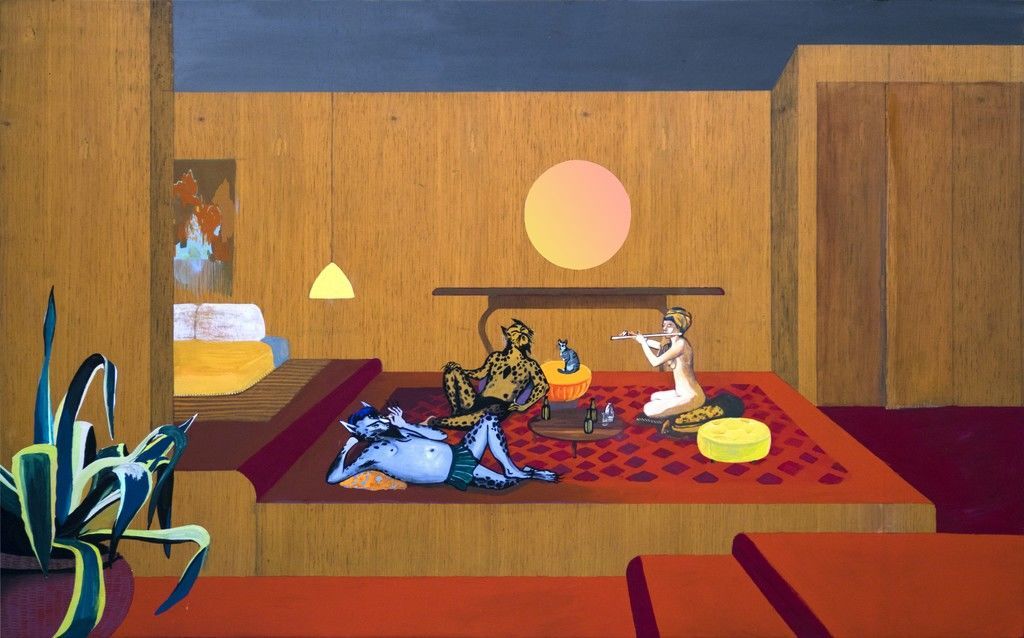

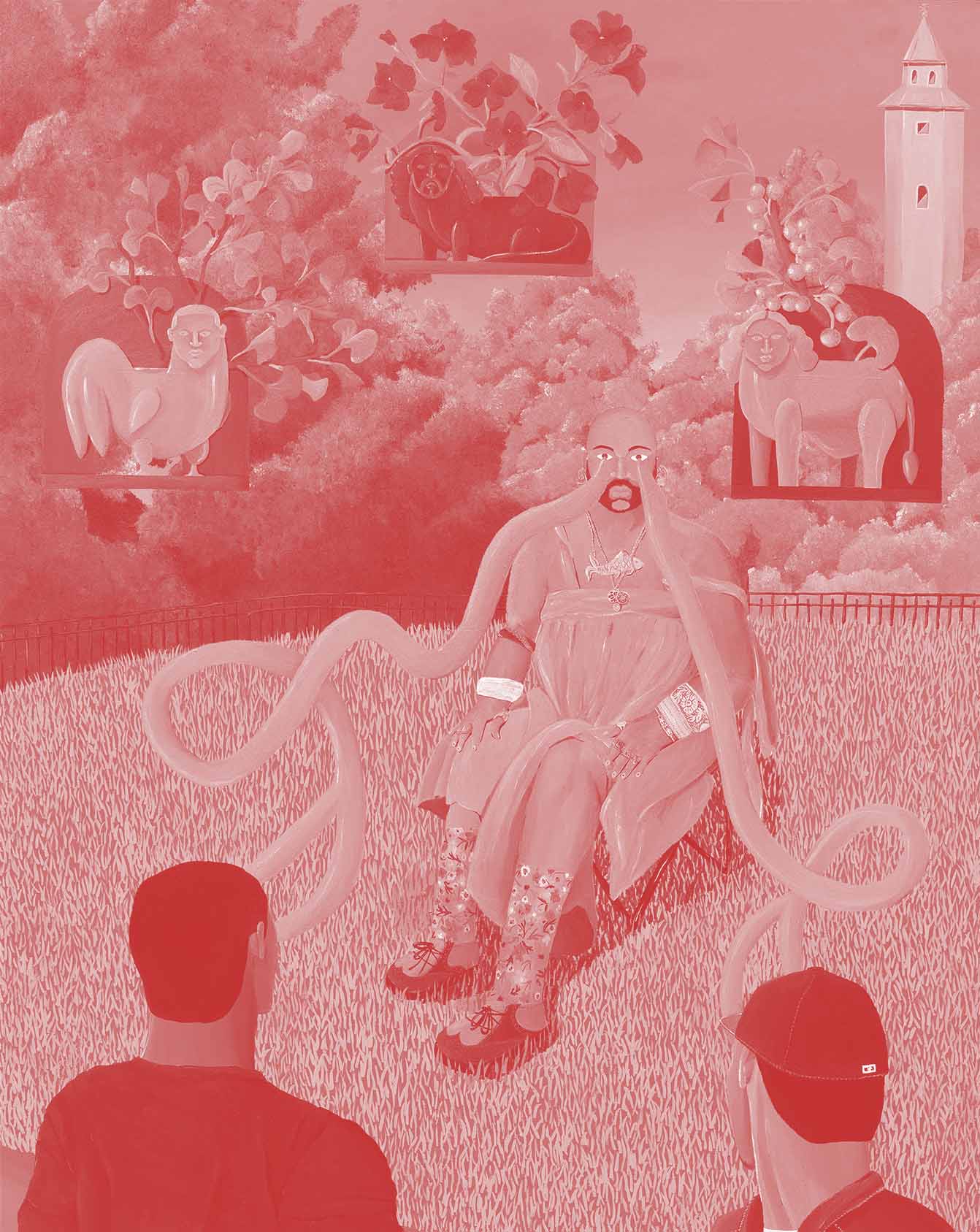

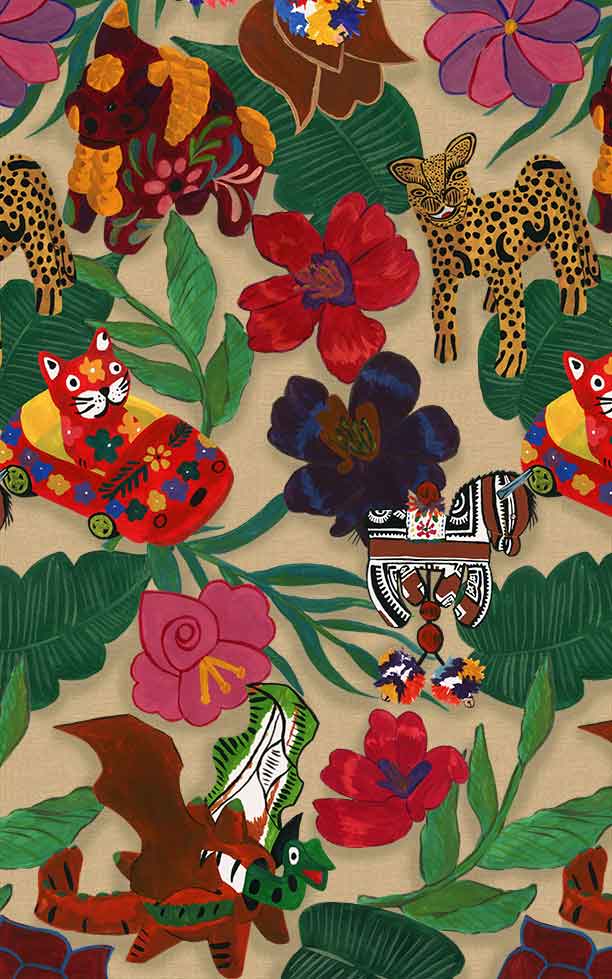

Con Melissa, fue un viaje exploratorio que iba desde el steam punk, hasta un retrofuturismo tropical, tuvimos largas conversaciones de todo tipo, hasta crear una amistad tan hermosa que no nos daba vergüenza llorar ante nuestras emociones que fluían a la hora de curar, poder acompañarla en su primera gran exhibición para mí fue un honor, no solo por su innegable talento sino por el gran ser humano que es.

¿Qué cambio has notado en la escena de arte en RD desde el momento que empezaste tu carrera hace más de 10 años?

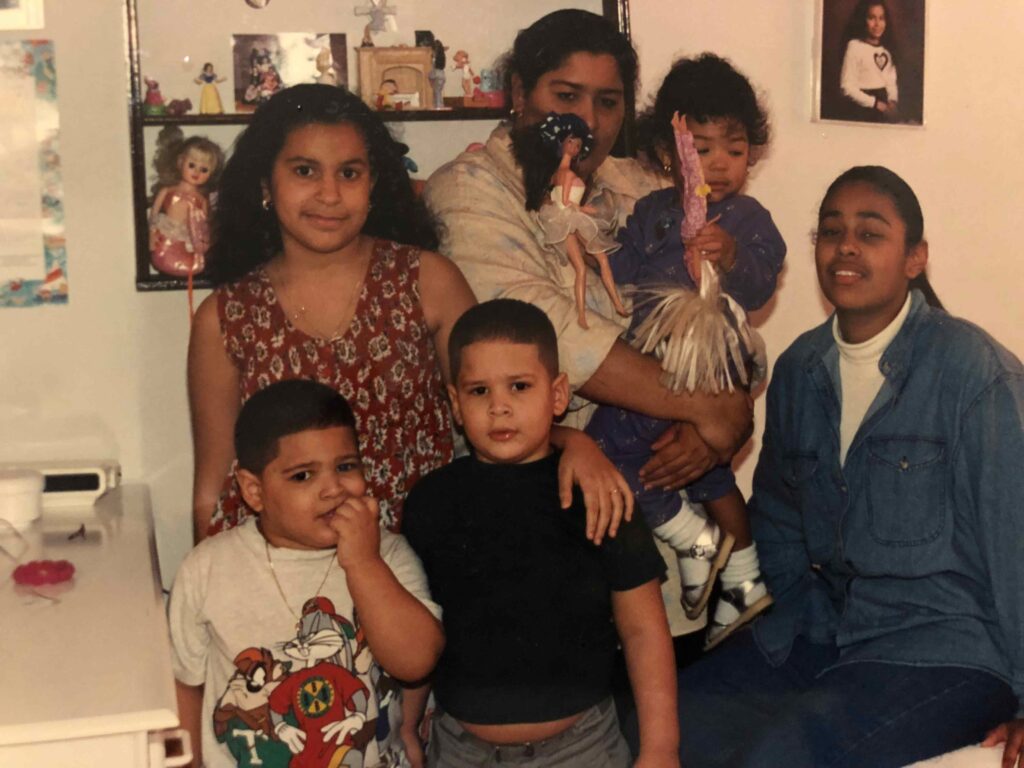

Muchísimo, a partir de Curando Caribe un buen grupo egresado de este programa toma la escena local y prácticamente deconstruye y reconstruye no solo el aspecto visual desde las narrativas visuales establecidas, sino propone nuevas maneras de como replantear una muestra, tanto en lo sociológico, antropológico y con ello nuevas filosofías en aspecto museográfico, museológico y narrativo al establecer un contacto mucho más amplio por los medios que manejamos hoy en día con el artista y su obra, escuchar sus historias, sus contextos de vida, sus sueños, sus temores y fracasos, establecer nuevos formatos en lo contemporáneo, como una manera de encontrar y contar la verdad.

¿Cuál es la mayor lección que has aprendido a lo largo de tu carrera?

Nunca hacer nada con lo que no estés de acuerdo por quedar bien con los demás, hay que ser honesto, sobre todo con los valores y principios que debemos poseer, escoger bien nuestros artistas, trabajar con ellos y apoyarlos no solamente porque sean talentosos, sino porque sean íntegros, comprometidos y mejores seres humanos.