Scherezade García is a celebrated artist whose work delves into themes of migration, history, and cultural colonization. Drawing from her Caribbean roots, she explores the impact of the 1492 events on identity and race, using vibrant visuals to challenge traditional narratives. Her influence extends beyond art, fostering collaboration and community. In this conversation, discover how her work seamlessly blends personal and global stories, offering a powerful reflection on resilience, transformation, and the richness of the Dominican diaspora.

Your work explores themes of migration, history, and cultural colonization. How do these subjects influence your creative process, and why are they central to your artistic expression?

These subjects are not influences of my work; they are the core values of my visual discourse. I am from the Caribbean, and I am fascinated by the history of the so- called New World and the 1492 events that drastically changed our conception of the world and redefined the limits of geography. Also, the resulting genocide, and the expressions of resistance and resilience, and tactics of survival of the Native Americans, African slaves and even the Spanish criollos are endless sources of inspiration and an essential part of my visual discourse. This interest has led me to explore themes about global migration, the politics of inclusivity and race, the questioning of religious and social notions of paradise, the search for a hybrid salvation as a consequence of colonization, and the resistance against transplanted values that are transformed in Las Americas. It is a history imbedded in movement, encounter and transformation. The joy, the beauty, the best tools for resistance and survival.

As a co-founder of Proyecto GRÁFICA, a printmaking collective of artists of Dominican descent, can you share how this collective has shaped your perspective as an artist, and what role collaboration plays in your artistic journey?

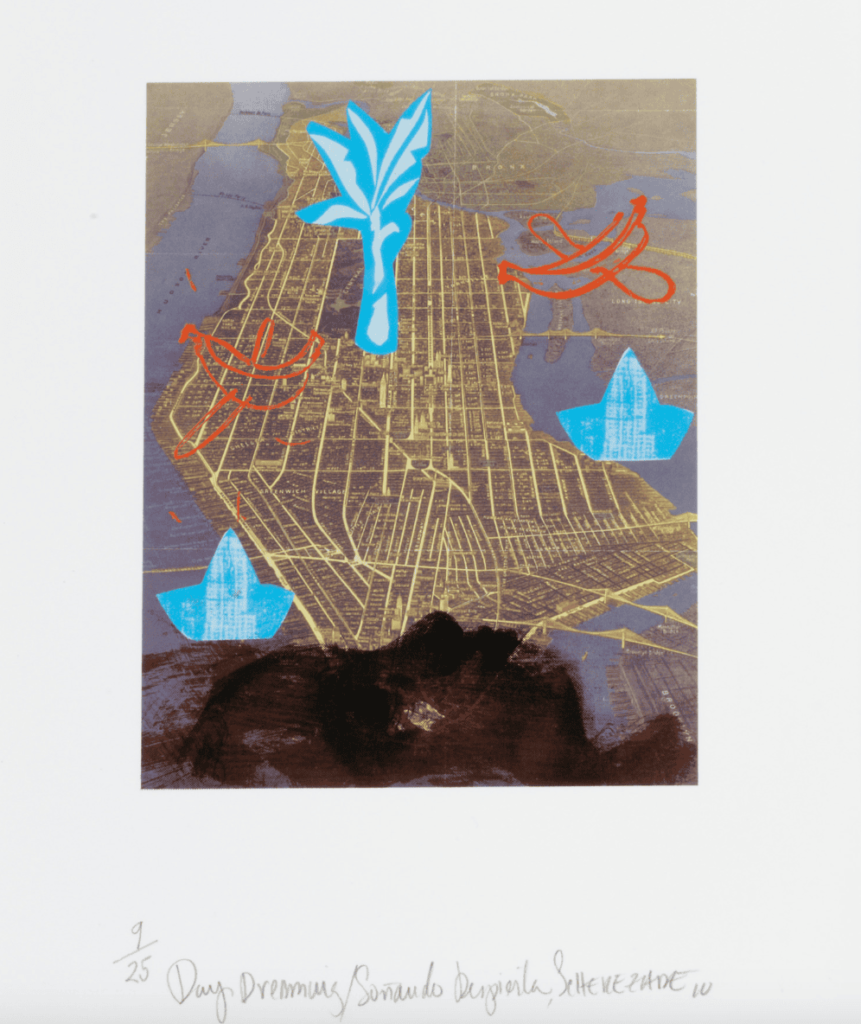

I cherished my time as part of the Dominican York Proyecto Gráfica (DYPG). When I first arrived in New York City to continue my studies at Parsons, I had the privilege of encountering the iconic artist, performer, and author Josefina Báez (known for Dominicanish, 1987). Not long after, I met the late visual artist, Freddy Rodríguez. Though I was quite young, I had already connected with a community of artists in Santo Domingo. Among them, a dynamic group of artists and designers from Altos de Chavón made me realize that achieving anything meaningful requires a supportive community. Later, I met artists and scholars of Dominican descent through a collective that organized the “Dominicans 2000” conference. Key figures like Dr. Silvio Torres-Saillant, Daisy Auger-Dominguez, Dr. Edward Paulino, Julia Alvarez, Moses Ros, Iliana Emilia García, and Carolina Gonzalez were among those involved. Our meetings, held at City College (CUNY) in the late ’90s, solidified my belief in the importance of community building, and it established my love for the Dominicans in NYC, and I embarked in series like “Morir Soñando 2008” and “Paradise Redefined” 2004-2007) see in my website.

Joining DYPG felt like a continuation of a model that many of us had already experienced. By then, I had spent over a decade engaging with the “Dominican York” experience, which had become a central discourse in my work. The DYPG initiative was indeed a groundbreaking project, yet, as I’ve often expressed, it was deeply informed by earlier efforts that paved the way for its success.

Your installations and paintings have been featured in prestigious exhibitions and biennials worldwide. How do you navigate the balance between creating art for a global audience while staying true to your Dominican roots?

I am Dominican, Dominican York, proudly Pan-Caribbean, and from this Side of the Atlantic which makes me inherently global. As a young artist from a family deeply engaged in politics and the history of our island and las Americas, I have a profound understanding of my roots. This understanding is fluid and constantly evolving, allowing me to connect with the many layers of my skin. I feel a sense of belonging to multiple “homes,” and because of my rich, plural heritage, I can embrace a global perspective. Through my hybrid background, I can truly embody globalization. We are the future.

In your work, memory and collective identity play a pivotal role. How do you view the relationship between personal memory and broader cultural narratives in the context of the Caribbean and Dominican diaspora?

I explore the relationship between personal memory and broader cultural narratives within the context of the Caribbean and the Dominican diaspora, starting from the personal, which is inherently shaped by the collective. My process involves extensive reading and research, engaging in conversations, and then allowing myself to fabulate—exercising the imagination and envisioning utopias. The “diasporic” experience is visually and linguistically, rich, offering endless sources of inspiration that intertwine the personal, collective, and imaginative.

As a board member of the College Art Association and a member of several arts’ advisory councils, what changes or developments would you like to see in how the art world engages with artists of Latin American and Caribbean descent?

What a thought-provoking question! Thank you!

This topic can lead to extensive discussions, as I am neither a magician nor a prophet! I’m grateful for the opportunity to serve on the boards of various organizations, some of which have historical significance and have undergone countless transformations to adapt to the changing times and power dynamics. Others are newer, working to establish their core missions.

Through these experiences, I’ve learned valuable lessons, as well as faced some disillusionments. One important lesson that comes to mind is that none of us are perfect; our main challenge lies in embracing diversity authentically and sincerely. Changing the frameworks of the art world and societal perceptions is a slow and significant endeavor, but it is worthwhile. We may encounter unexpected allies and pleasant surprises, but I have also witnessed self-loathing within our community. Much work lies ahead. To foster genuine changes in how the art world engages with artists of Latin American and Caribbean descent, we must understand our history and avoid becoming what we criticize. We need to remain open to unorthodox ways of sustaining our practices and truly supporting artist communities, rather than advancing our individual careers at the expense of those who came before us or collaborating with celebrity culture that offers only superficial fame. Additionally, we have a responsibility to practice what we preach, as meaningful changes are essential in the art world. Many artists speak about the need to decolonize, yet these same individuals often embrace the very values we seek to challenge. In conclusion, we have a great deal of work to do!

Can you tell us about the role of your “Cinnamon Figures” in your paintings? What role do they play in challenging traditional views of nationhood and inclusion?

Race and the politics of color (formally and conceptually) are essential to my work. The cinnamon figure has been a constant in my work since 1996. Mixing all the colors in a palette is an inclusive action; the outcome of such activity is cinnamon color. The new race, represented by my ever-present cinnamon figure, states the creation of a new aesthetic. This unique aesthetic with new rules originated from the lush landscape, the transplantation, appropriation, and transformation of traditions. Also, the catholic iconography with my mixed-race warrior/angels is a way of colonizing the colonizers by appropriating, transforming, and creating new icons. All a consequence of the movement and encounters in the Caribbean waters.

.